Experts say investors are driving up housing prices as they own over 50% of Toronto’s new condos

Jaqueline Belardi doesn’t know if she’ll ever be able to afford a home even though she earns a good salary. Belardi and her partner make a combined income of more than $180,000, but saving up enough money for a down payment feels out of reach.

“We can’t just borrow $50,000 from our parents,” she said. “That seems like the only way younger people are able to buy property these days.”

The more rent she pays, the less she’s able to save up. The couple pay $2,750 for rent in their 1970s west-end Toronto apartment building, designed in an era of government housing that prioritized spacious units. Belardi, 35, and her partner would love to buy an apartment in the building but their mortgage costs would be double what they currently pay.

“We think maybe we’ll just rent here forever, but then you’re at the whim of your landlord,” she said. “You see some landlords own 10 properties and here we are with a good income unable to buy an apartment. People deserve to buy a home if they want to.”

Experts say real estate has become a game, where investors rather than end users are the main players, buying and selling property to cash in on Toronto’s hottest commodity. In the process, they’re driving up prices and pushing out prospective homebuyers like Belardi, who just want somewhere to live.

Investors’ hold on real estate has become hard to ignore, leading the Bank of Canada and even Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to call them out for the commodification of housing.

However, insiders say both federal and provincial governments as well as the central bank share blame in creating the conditions that allowed investors to corner 20 per cent of the market in Ontario, including 80 per cent of pre-construction condo sales and 57 per cent of newly built condos in Toronto.

The result, they say, is not only a real estate market where an income of more than $200,000 is needed to even get a seat at the table and prospective homeowners burdened by ever rising rents are unable to save up for a down payment, but also a system where investors dictate what gets built — and what doesn’t — and over-leveraged multi-property owners can weaken the overall health of the market.

From co-ops to condos

The roots of Canada’s housing crisis goes back decades, experts say, stemming from the federal government shirking responsibility for building affordable housing.

From the 1950s to 1970s, Ottawa constructed tens of thousands of nonmarket homes, said Dania Majid, a lawyer with Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario (ACTO).

But the financial crisis in the 1980s and recession in the early to mid-1990s led to austerity measures and stricter budgets, Majid said, which meant cutting back on social services and housing initiatives.

Facing substantial deficits, in 1992 the government cut the federal co-operative housing program, which had led to the construction of nearly 60,000 homes, and eventually the federal government stopped building any affordable housing.

“Unlike many European countries, Canada very early on decided the private market would be the one responsible for providing housing,” said Majid.

Condos became the main housing type to get funding from the private sector. The units were small and therefore cheaper to build, and could be sold for maximum profit.

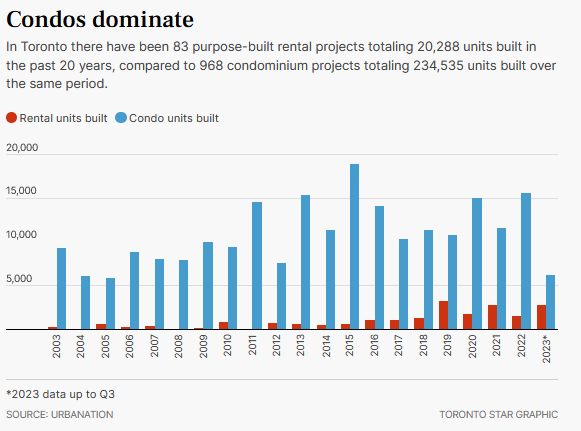

In Toronto, there have been 83 purpose-built rental projects totalling 20,288 units built in the past 20 years, according to research firm Urbanation. This compares to 968 condominium projects totalling 234,535 units built over the same period.

“Condos are a relatively more affordable investment as they’re cheaper to buy and maintain compared to a single-family home,” said Marc Desormeaux, principal economist at Desjardins, noting investor demand has remained concentrated in that segment of the market.

Universal rent control ends

The housing crisis wasn’t born overnight but began decades ago when government “got out of the housing business,” said Nemoy Lewis, assistant professor at the School of Urban and Regional Planning at the Toronto Metropolitan University.

“Because of this, the private market grew and filled the void of both levels of government — federal and provincial,” said Lewis, allowing non-traditional landlords such as private equity firms, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), asset management firms, and public pension funds to claim a greater stake in the sector.

According to Lewis’s research, from 1995 to 2022 financialized landlords accounted for 65 per cent of all multi-family dwelling units transacted in Toronto, which “coincides with a drastic jump in real estate prices for apartments,” he said.

But in the late 1990s, a pivotal moment took place that created the perfect “breeding ground” for investors, Majid said.

In 1997, former premier Mike Harris passed Bill 96, which removed rent control for units first occupied after Nov. 1, 1991.

His government also instituted new regulations that unshackled landlords from unprofitable regulatory restraints in place since the mid-’70s. Under the change, landlords would be allowed to raise rents to match market rates whenever a tenant moved out. Previously, landlords had a limit on raising rent between tenancies.

“This is what created the foundation for investors,” said Majid.

“Vacancy decontrol attracted investors to get into the market. We have this perfect storm as we get a flatline in affordable housing being built, as well as the private sector not building enough, but demand continues to skyrocket, pushing up rents and home prices.”

House prices soar

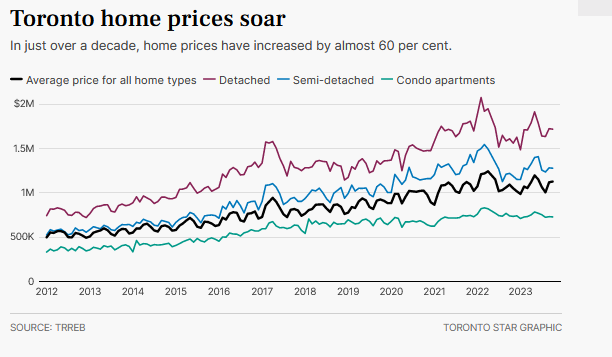

In 2010, the average home price was $430,000, according to the Toronto Regional Real Estate Board (TRREB), and in October 2023 it reached $1.12 million, meaning prices have skyrocketed by more than 160 per cent in just over a decade.

The rapid boom in home prices is the biggest reason for investors piling into the market, said John Pasalis, president of real estate brokerage Realosophy, and that has largely been aided by low interest rates since the 2008 financial crisis. The Bank of Canada kept the overnight lending rate below two per cent for more than a decade.

“Homes prices were steadily increasing in Toronto for years,” Pasalis said. “Before 2015, home prices were appreciating at around six per cent every year.”

But a quick acceleration in prices after 2015 led to home prices appreciating much faster. Average prices were up 33 per cent year over year in March 2017, largely due to a surge in demand from investors buying homes, primarily in the suburbs, he said. While the Bank of Canada had low rates at the time, it can’t fully account for the substantial price jump, he added.

Because prices rose quickly, more investors dove into the market, Pasalis said, wanting to reap the benefits and gain more capital.

“There was a sentiment shift during the market at that time,” he said. “It felt like the time to buy an investment property and so people piled in.”

Rent control killed again

As the market heated up, it spurred former premier Kathleen Wynne, in 2017, to implement rent control for all properties occupied on or after Nov. 1, 1991, essentially reversing Mike Harris’s policy.

But a year later, newly elected Premier Doug Ford pulled rent control for new builds saying the move would provide “incentives” for the private sector to build more housing.

He enacted legislation so that rent control would only apply to rental units created and occupied prior to Nov. 15, 2018 — meaning new buildings, additions to existing buildings and most new basement apartments that were occupied for the first time for residential purposes after this date would be exempt.

“The problem is these incentives weakened tenant protections,” Majid said. “And any new supply coming onto the market isn’t rent controlled, continuing to push prices higher.”

Since 2015, home prices have doubled in Toronto. But the biggest home price acceleration was experienced during the pandemic when the Bank of Canada lowered the overnight lending rate to 0.25 per cent for two years, making it cheap for investors to borrow money.

A lending practice that became popular during the pandemic was the home equity line of credit (HELOC) — a revolving type of secured credit with a maximum credit limit, where the collateral is the borrower’s property and it requires interest-only payments. When interest rates hit historic lows, HELOCs had interest rates below 3 per cent, Butler said, which was “unheard of” until that time.

What had typically been a lending vehicle to help with home renovations became an “influencer” in investor activity, he said, with some homeowners using the loans to pay for down-payments on other properties.

According to Statistics Canada, in February 2022 a 10-year record was broken when Canadians borrowed an additional $2 billion on HELOCs — the highest one-month increase since 2012.

There was “excessive” froth in the market, Butler said, as investors speculated and flipped properties, ramping up prices until the market reached its peak in February 2022, when the average selling price for a home hit $1.33 million.

In just three years, investors’ share of the country’s mortgaged homes rose from 20 per cent to 30 per cent, according to the Bank of Canada.

It’s an investor’s game now

Today, nearly 40 per cent of homes constructed since 2016 in Toronto are investor-owned, with investors possessing 56.7 per cent of the condos constructed in the last six years. The majority of condos built before 2016 are all predominantly owned by non-investors, according to Statistics Canada. Twenty per cent of Ontario’s homes are investor-owned.

Around 80 per cent of pre-construction condos are sold to investors as condos have proved lucrative, appreciating by hundreds of thousands of dollars in the last 15 years, Desjardin’s Desormeaux said. Because of this, they’re now driving the type of housing stock being built in Toronto, which are not designed for families in mind.

“We’re missing that midrise density, with bigger apartment units that allow for more variety of housing in the city,” he said. “We need more of that type of housing, which can be done with increased densification.”

Experts say that when investors dictate too much of the market it can create more volatility, as a large segment is at their whim. And when interest rates go up, landlords tend to off-load the higher costs to tenants, or force evictions to raise rents, TMU’s Lewis said.

As the market has cooled, investors — win or lose — are the ones still in the game. Butler said that as interest rates have soared new listings have been largely driven by over-leveraged investors who need to sell. At the same time, cash-strapped investors are still able to buy in a high-interest rate environment because they’ve managed to secure enough capital over the years, as opposed to prospective first-time buyers.

For policymakers, investors’ stronghold in the market has become too blatant to ignore.

“We do know that one of the factors that is challenging for so many people is the commodification of housing (and) the fact that people are using homes and houses as an investment vehicle — particularly corporations using homes as an investment vehicle — rather than families using them as a place to live, grow their lives and to build equity for their future,” Trudeau said in late October.

The federal government is starting to crack down on revenue streams for investors, unveiling new tax measures to remove incentives for people leasing short-term rentals and providing funds to help crack down on those not in compliance with local laws.

To ensure more homes are in the hands of end-users, housing advocates say the first legislative change needed is for the province to reinstate rent control on all properties and to have rent control between tenancies.

“Vacancy decontrol incentivizes landlords to kick out tenants to raise rent for the next tenants,” Lewis said. “We need to have rent controls in place to keep rent affordable.”

Cracking down on short-term rentals and “ghost hotels” is imperative, said Pasalis. Some economists have even said governments could outlaw Airbnb and other short-term rental platforms in big cities for five years to shore up housing while providing “some breathing room” for new builds.

“The only way to market pre-construction condos for a while was to market them as short-term rentals to make the numbers work because you could make more money per month with short-term rentals than long-term tenancies,” Pasalis said. “That certainly has contributed to price appreciation as some professional landlords have pools of short-term rental properties.”

Clamping down on home “hoardership” should also be studied, said Majid, as insurance companies such as government-owned Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corp. could refuse insurance if someone is seeking a mortgage on a 17th property.

And the federal government can build more housing and be less reliant on the private sector, she said, as the public and private sectors operate in fundamentally different ways.

“The for-profit sector needs to meet the expectations of their shareholders. Governments are responsible to the residents that they serve. Those are two different priorities,” Majid said.

“There needs to be a transformational change of how we provide and maintain housing. The government needs to build nonmarket housing like how it did before the 1990s. To look at housing not as a commodity, but as a fundamental human right.”

This article was reported by The Star