Ottawa to reduce the share of temporary residents to 5 per cent in the next three years

The federal government’s move to restrict the number of temporary residents in Canada will cool demand in the beleaguered housing sector and help in the battle against inflation, according to some economists.

On Thursday, Ottawa announced that it will reduce the share of temporary residents to 5 per cent of the total population from 6.2 per cent over the next three years.

This means the volume of temporary residents will drop by roughly 20 per cent from the current 2.5 million, although the plan will be finalized by the fall, Immigration Minister Marc Miller said.

While the government sets annual targets for its admissions of permanent residents, it has not previously done so for the category of temporary residents, although earlier this year, Ottawa announced a two-year cap on the issuance of visas to international students.

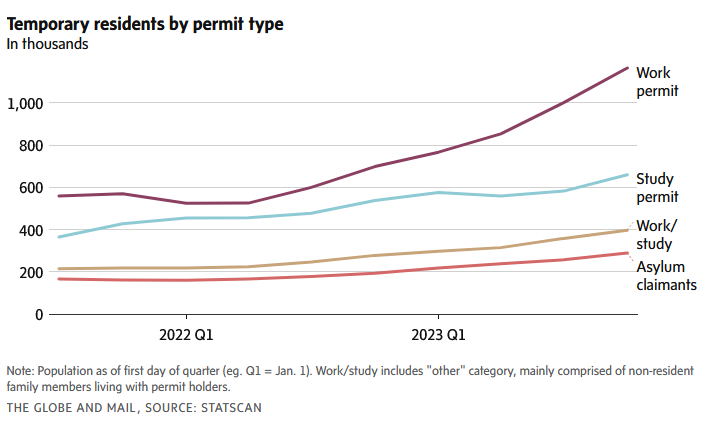

The ranks of temporary residents – a group that also includes people here on work permits – have exploded over the past two years, leading to widespread criticism from economists that Canada is struggling to absorb this spike in newcomers.

“I think it’s a big move,” said Robert Kavcic, senior economist at Bank of Montreal. “This is attacking the demand curve now, which is a complete change in philosophy for policy makers, and one that we think is actually going to work.”

Mr. Kavcic estimates that population growth will ebb closer to 1 per cent from recent levels in excess of 3 per cent. This would bring growth more in line with historical rates.

The Canadian population grew by around 1.25 million or 3.2 per cent over the 12 months to Oct. 1, 2023. Not only is that the fastest expansion since the late 1950s, but it sets Canada apart from other wealthier countries. Most of the recent increase in population has been driven by temporary residents, many of whom aspire to settle permanently.

The federal government has long maintained that stronger immigration is needed to counter the effects of an aging society and to fill labour shortages, which employers have openly complained about. But Ottawa has conceded that recent growth is exacerbating some issues, such as access to housing and health care.

Economists at BMO have argued for years that Canada’s protracted housing crisis was not merely a supply-side issue, but that demand factors have also contributed to the sharp rise in prices.

Mr. Kavcic said that efforts to boost housing supply can take years to materialize. “Whereas with the stroke of a pen, Ottawa can pull the demand curve back overnight,” he said. “And it seems like that’s what they’re gonna do.”

Bank of Canada officials have often noted that immigration has a neutral effect on inflation over the long term, because those newcomers are both consumers and workers. However, in recent months, the bank has acknowledged that imbalances in the housing market can lead to higher shelter price inflation, which is currently a headwind for the bank as it seeks to bring inflation back to its 2-per-cent target.

“Most newcomers rent when they first arrive in Canada, which pushes up demand for rental housing and can lead to short-term pressure on rent inflation,” deputy governor Toni Gravelle said in a speech in December.

Shelter prices have risen 6.5 per cent over the past year, with rents up 8.2 per cent, compared with headline inflation of 2.8 per cent in February. And while Canada has struggled to build sufficient rental housing over decades, the recent rush of demand has pushed vacancy rates down to historic lows, according to Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp.

“The cap on temporary-resident admissions isn’t a silver bullet since supply and demand in the housing market are currently extremely imbalanced,” Royce Mendes, head of macro strategy at Desjardins Securities, said in a note to clients. “However, by way of just slowing the upward momentum in shelter inflation, this reinforces our view that the central bank will cut rates more forcefully than” investors are predicting.

Also on Thursday, the federal government announced a partial curtailment of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. Starting on May 1, employers in four sectors, including hospitality, will see the share of staff they can hire through the program’s low-wage stream lowered to 20 per cent from 30 per cent. (Employers in health care and construction will be exempt from the reduction.)

Most employers are subject to the 20-per-cent cap, which was raised from 10 per cent as part of a 2022 overhaul of the program. At the time, the government set a temporary 30-per-cent limit for a handful of industries with acute labour shortages.

“We are disappointed in the announcement on temporary foreign workers, as this will make it even more burdensome to fill the current 100,000 job vacancies in the food-service industry and create more red tape,” Kelly Higginson, president and CEO of lobby group Restaurants Canada, said in a statement.

“Ottawa should be careful when placing arbitrary caps on immigration,” Diana Palmerin-Velasco, senior director on the future of work at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, said in a statement. “Temporary residents, including temporary foreign workers, can be a critical pool of talent for some sectors of our economy.”

Rebekah Young, head of inclusion and resilience economics at Bank of Nova Scotia, said Thursday’s announcements were largely “backward-looking,” in that Ottawa is trying to manage the accumulation of temporary residents.

Ms. Young said the federal government needs to articulate its objectives for economic immigration. As an example, she said those goals could be tied to gross domestic product per capita, which has tumbled to multiyear lows of late.

“That gives you a hard metric to evaluate all your programs,” she said.

In theory, the new limits on temporary residents will marginally change the relative cost of labour versus capital, Ms. Young said. However, business investment in Canada has been weak for a long time, predating the population surge.

“We need more of a productivity agenda that looks at what are the really big levers to unlock substantial business investments,” she said. This “is ultimately what will drive welfare gains.”

This article was first reported by The Globe and Mail